“What if you’re in the book and I don’t represent you the way you like?” asks Jacob, a past-his-prime graphic novelist, of Alison, a young art student, in the first season of Easy.

“That’s fine by me,” she says, cocking her chin upward. Alison, portrayed by a platinum blonde Emily Ratajkowski, is one of three people who has come to see Jacob speak about his latest book, a cartoon on his descent into art world obscurity. They continue drinking at his apartment, where she seduces him without fanfare on the couch.

In the morning, careful not to wake him, Alison takes selfies in bed as Jacob snores beside her. She pads through his apartment in sheer tights and a bra, splaying her body about his furniture and snapping photos with precise clicks on a selfie stick. She sees herself out.

Later on, at Alison’s gallery show, Jacob is shocked to discover a picture of himself, near-naked and hungover, displayed among her series. He’s appalled that she’d take—much less publish—intimate pictures of him without his consent.

“It’s like date rape!” He yells at her in front of an assembling crowd. “You didn’t ask me. You were in there, and I was sleeping. I didn’t know you were taking that picture!”

“Did you draw me?” she asks coolly, crossing her arms in front of her chest.

Jacob shrugs, defeated. “Yeah, I drew you.”

She raises an eyebrow. “Did you ask my permission?”

—

Five years later, the Easy episode functions as almost too-perfect foreshadowing of the themes at the heart of Emily Ratajkowski’s September 2020 New York Magazine essay, “Buying Myself Back.” In it, she chronicles the many ways she’s been exploited throughout her modelling career, mostly by men who have profited off of her image without her explicit consent, whether via lawsuits over social media posts, being forced to buy back photos of herself from ex-boyfriends, or having no legal say in the publication of presumed outtakes.

The essay is packaged as an investigation of the question, Who has a right to their own image?, but somehow, we never actually get there. Instead, the entire issue is eclipsed by the plot of the piece: In what is positioned as the climax, Ratajkowski recounts being sexually assaulted by the photographer Jonathan Leder after a slippery-slope portrait session; years later, Leder sells multiple books of the unpublished, uncompensated Polaroids from the shoot.

By the end of the essay, we’re meant to feel that Ratajkowski alone deserves to set the terms around reproductions of her own image, though not because she’s rigorously engaged with IP law, theoretical approaches to the issue of image ownership, or even her own airtight analysis. Instead, she makes her case by liberally applying the rhetoric of consent—originally reserved for conversations about actual sex—to mediations of and even conversations about the body. As such, the signposted power dynamics in the story (gender, successful career photographer and naive young model, the amount of money on the table) are intended as evidence of her inherent exploitability.

That Ratajkowski’s argument largely relies on the conflation of harm caused to the body with harm caused to representations of the body is striking in and of itself, and may expose an internalized cultural understanding of metaphorized “violence” as material violence. The ease with which the essay slips from its would-be discussion of image ownership to one of sexual assault suggests that the two are seen as points on a continuum, if not as the same thing.

But it’s crucial to take image ownership as a standalone issue—without the separate concern of sexual assault—as doing so unearths other, thornier implications of lobbying for total control over one’s image (both for Emily Ratajkowski, and more generally for ourselves). What’s more, it reveals that the most urgent matter (and perhaps the one that Ratajkowski was actually after in the first place) is the inverse: not quite the right to one’s image, but the right to one’s lens.

The question of what constitutes Emily Ratajkowski’s image is, on its own, difficult to pin down. In the objective, material sense, she is an extremely beautiful woman: heavy-lidded “fox” eyes; pouty bow-shaped lips; Barbie-esque tits that seem almost cyborgian, given her impossibly low BMI. Ratajkowski’s beauty alone is something to behold, but of course, her “image” is not constrained to her physical form: The real value proposition rests in her inexplicable effect. Early on in her career, she maintained a playful vacantness that lent itself to sexual fantasy; over time, she’s exacted a more fiery persona with her overt self-objectification and simultaneous demand to be seen as an intellectual.

In the years since the events described in the New York essay, the value of Emily Ratajkowski’s “image” has greatly appreciated. The 2012 Leder shoot, for which she was “paid” in exposure only, occurred well before her breakout appearance in Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” video, a performance that bloated her literal and figurative worth. Today, Ratajkowski has achieved sex symbol status, with all the attendant signifiers of modern, monied female power. While she has somewhat preserved her persona as an accessible downtown girl—her #HotGirlsForBernie Instagram presence, case in point—she is, ultimately, a businesswoman. Between her swim-and-clothing line, a forthcoming book of essays, and her recent NFT auction sale, Ratajkowski has squarely earned the now-disgraced title of “girlboss”—she’s just one whose brand largely begins and ends with herself.

As Ratajkowski has added new mediums to her performance arsenal (from pure modelling to acting, designing, and most recently, writing) her image has become more abstract—and, critically, more omniscient. Today, a discussion about Emily Ratajkowski’s “image” is less about what she looks like than it is about what she represents; in turn, each new venture—and each new post—serves to further inflate and refine her persona, and also to control her reception. In both theory and practice, Ratajkowski’s ethos is perhaps best epitomized by her own business’s tagline: “Inamorata is all about being your own muse.”

—

“A woman must constantly watch herself,” writes John Berger in his 1974 book Ways of Seeing. “From earliest childhood she has been taught and persuaded to survey herself continually… And she comes to consider the surveyor and the surveyed within her as the two constituent yet always distinct elements of her identity.”

While Berger was proffering an oversimplified argument about socialized difference between the sexes, the duality he describes is perhaps most literalized in the vocation of modeling. Given that a model is uniquely tasked with consciously objectifying herself, she at once possesses a heightened awareness of herself as both subject and object. To a certain extent, the strength of her craft resides in her ability to obscure the labor required to self-objectify; to that end, her appeal is in large part determined by her own self-erasure, by the willful blotting out of her own subjecthood to make room for others’ projections.

In this way, the subject/object relationship has the potential to produce a third entity: the vessel. Neither active nor passive, an effective model creates a designated space for fantasies to move through. This there-less-ness is critical, and worth protecting.

The democratization of image-making has, by its very nature, introduced complications to this process. Firstly, it has bloated the functional definition of “art” to include any stylized images—editorial, advertisement, and even personal posts on Instagram—insofar as we seek them out as an escape from the mundane. But more importantly, the cheap tools and lightweight distribution channels of social media have emboldened us to seek an unprecedented degree of control around the way we appear to others, both in a material, photographic way, and as a larger, nebulous person-concept.

On the one hand, inserting the self back into the equation may eschew any unwelcome outside gaze and, in its place, allow us to re-author our own personal (albeit public-facing) narratives. On the other, this single-actor, closed circuit of author and subject may foreclose the possibility of creating any sort of compelling emotional conduit. As a result, today’s mass-circulated images, while beautiful, often decline to evoke much of anything at all.

—

Given her current position within the cultural consciousness, the question of who “owns” Emily Ratajkowski’s image seems rather obvious: She does. But now that she has successfully reclaimed her own likeness for profit—and has extricated herself from business dealings with the likes of Jonathan Leder, those who would profit directly off the exploitation of her image—Ratajkowski has saddled herself with a far greater task: controlling public perception, another “image” that is ultimately out of her control. With this in mind, her new fleet of offerings and exposure is less a break from the commodification she endured as a model than it is a pivot, PR-style, toward a new aesthetic that seeks to code her as an intellectual, a political actor, and perhaps most perniciously, an artist.

As such, Ratajkowski exists as one of the highest-profile manifestations of Instagram-age self-determinism, under which the production of identity-bound images is re-imagined as a route to personal empowerment. Money-making opportunities aside (which are ultimately far less important), EmRata’s ascent as a public symbol simply reflects the larger cultural idea that one can (and should) seek inspiration primarily from the self—and furthermore, that one is entitled to full control over their own connotation, regardless of how they might be naturally perceived.

Taken at scale, the consolidation of power between image and lens ownership does incur real damages. In effect, this new means of production adopts a sort of circular reasoning that seeks to make both its method and its products unassailable by insisting on the validity of personal choice, regardless of what those choices may be. In prioritizing self-expression and self-actualization, artists (which we might understand liberally to mean all “creators”) are relieved of the duty to make something of value for (or engage with ideas about) anyone outside of themselves. Moreover, the dynamic serves to anticipate and repel all criticism—not only of message, but also of actual artistic skill.

—

In his 2008 book, The Photograph Commands Indifference, Nicholas Muellner writes that “the monument is inextricably caught between its meaning and its being,” that the monument is valuable primarily for its function as an “idea-receptacle.” In its attempt to “insert the idea back into the physical,” he argues, the monument is like a photograph. So, too, is a model.

A model, like a photograph and a monument, exists as an emblem to a time that is necessarily no longer, a stand-in for an idea that has no other material manifestation—including a conception of itself. Therefore, a model “fails to transmit its idea” the same way a monument does when, in Muellner’s words, it attempts to “assert its physical self.” To demand to be seen as an agent, then, is necessarily to fail as a model.

The import of this failure is not just about the cheapening of a craft. Nor is it simply a longing for a less progressive era that had yet to demand women’s autonomy. Rather, this hyper-self-aware quest for control has produced a loss much less defensible by woke politics: We are witnessing the Death of the Muse.

This phenomenon is not restricted to expensive commercial art. The selfie, with the high-attunement afforded by filters and FaceTune, is perhaps the most pedestrian example. But in today’s diffuse personal branding landscape, any demand to be seen as both a respected individual and a fetishized symbol—launching a company, becoming an influencer, starting a podcast or Youtube channel or TikTok account—falls into the same larger category. Beautiful imagery has always proliferated alongside increased access to technology. But now, we’re consuming a higher concentration of highly curated images conceived of, manipulated, and distributed by the subjects themselves, rather than by an external visionary.

If repossessing one’s image is said to have made social gains and upended the institutional path to success (or at least, to celebrity), it has not been without costs. In collapsing the relationship between artist and muse, we’ve lost the sense of abstraction that has long sustained our yearning for—and faith in—art and beauty. The gulf of understanding, the space for illusion, the seductive quality of the unknown (which is to say, the possible) is snuffed out by the demands for clarity and communication.

Both meaning and the experience of meaning-making are diminished when packaged and delivered too neatly or too loudly. Beauty that over-announces itself, that dictates both what it is and how to handle it, belies its own self-evidence; this, combined with our innate allergy to things that feel too placed, has resulted in a loss of interest in so-positioned objects of desire. With no room to conjure our own fantasies of another—particularly if they might abrase the status quo—we find that there is little return on anything beyond the self; belief in nature, religion, beauty, and sex are all rendered trivial, if not downright regressive.

Muellner writes that monuments fail, ultimately, because they overstate what fundamentally cannot be stated: In their attempt to “restore the terrible racing away of meaning from subject,” they end up doing injustice to both. A model, likewise, cancels out her musedom and her personhood when she tries to restore the latter to the former, when she tries to transcend the limits of her form, in an effort to both do and be done to at once.

—

In December, New York announced that Emily Ratajkowski’s essay was the magazine’s most-read story of the year. This achievement perfectly exposes the well-greased, self-authenticating feedback loop of self-exposure, wherein our vain motivations are encouraged by the idea that sharing our experience is intrinsically a public good. Far from existing as a brave stand against misogyny, the essay’s virality merely exhibits our tendency to conflate vulnerability with virtue and, consequently, the vulgar social incentive to position oneself as screwed.

To take EmRata as a symptom of the worst forces that propel our society, such relentless self-narrativizing simply bares our insatiable need, newly internalized as a right, to simultaneously be depicted and to control those depictions. Worse still, the self-authored product is presented as sacrosanct, and any doubt cast on its value (much less its veracity) is taken as a “violation” not only of the work, but also of the maker. Ultimately, it is this particular grade of gluttony—not the desire to be seen in and of itself—that has produced our current brand of narcissism and, for that matter, gutted art of its potential to inspire, unite, or even provoke.

If we are to keep pursuing self-documentation, both as a means to connection and an artistic medium, we ought to consider inviting some ambiguity and authorial distance back in. At the very least, we might meditate on the idea that our image—what we represent, what we evoke—may actually hold more weight when logged, with care and proper technique, through the lens of another.

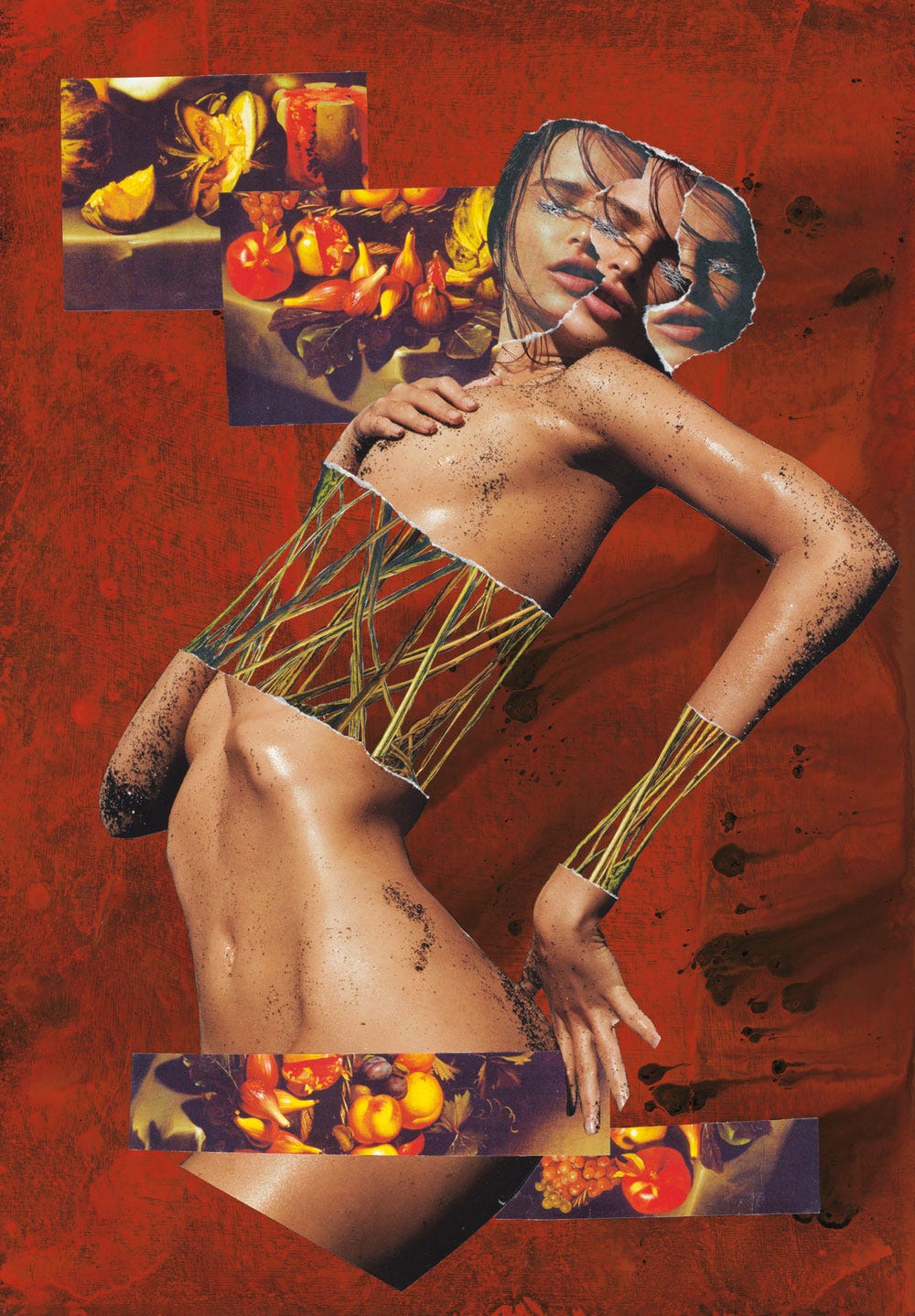

This essay appears in the first installment of Look Alive, a pamphlet series from Citizen Editions that pairs contemporary writing and images. You may purchase the pamphlet here.

Soooooo good, even better on the third read